Since the discovery of sudden boundary layer (BL) ozone depletion events about a decade ago, the chemistry of halogens in the troposphere has received growing attention. In 1986 Bottenheim et al., report periods of very low ozone concentrations during polar spring in Alert, Canada, 82°N. These low ozone events (LOE) were correlated with elevated concentrations of filterable bromine, giving the first indication that reactive halogen species (RHS) are involved in the destruction of ozone. Later Hausmann and Platt, 1992, report the first observation of BrO by Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS) in Alert, proving that RHS are indeed responsible for the complete depletion of BL ozone in arctic spring.

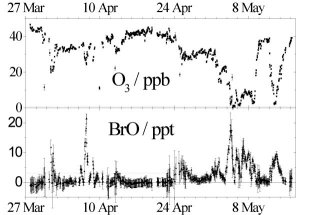

Since then several studies have confirmed these observations not only in the Arctic (Fig. 1) [Barrie et al., 1988 and 1992; Bottenheim et al. 1990; Tuckermann et al, 1997] but also in Antarctica [Kreher at al, 1996 and 1997]. Satellite observations show that regions with elevated BrO frequently extend over several million square kilometers [Wagner et al. 1998; Richter et al. 1998].

Figure 1: Ozone and BrO concentrations during a low ozone event in spring 1996 in Ny Ålesund, Spitsbergen [Tuckermann et al. 1997]

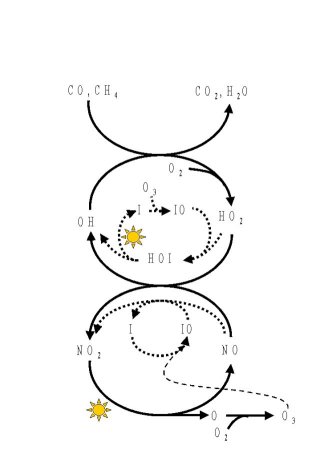

Two different chemical mechanisms involving RHS are responsible for the destruction of BL ozone [Finlayson-Pitts et al., 1992; Wayne et al., 1995; Le Bras and Platt, 1995]. The key species in both mechanisms are the halogen oxides XO and YO (X, Y = Cl, Br, I) which are formed in the reaction of halogen atoms with ozone (Reactions 1 and 2). In the self - or cross - reaction of the XO's and YO's the halogen atoms are recycled and can reenter the mechanism while an oxygen molecule is also formed. In total, cycle A converts two ozone molecules into one oxygen molecule without loss of RHS.

Cycle A:

|

X + O3 ®

XO +O2 Y + O3 ®

YO +O2 XO + YO ®

X + Y + O2

Net reaction: 2O3 (XOx = XO, X) (YOx = YO, Y) |

The rate of reaction (3) determines the effectivity of cycle A.

The second ozone loss process starts with the reaction of XO with HO2. The HOX formed is then photolyzed again, recycling a halogen atom. Together with the formation of HO2 by different OH reactions, this cycle also converts O3 into O2.

Cycle B:

|

|

XO + HO2 ®

HOX + O2 HOX + hn

®

X + OH OH + CO, O3 or VOC ®

HO2 + products

Net reaction incl. reaction (1): O3 (HOx = OH, HO2) |

Reactions 4 and 5 also have a strong influence on the ratio of OH/HO2 [Jenkin 1992; Platt and Janssen 1996], as will be discussed later.

The destruction of ozone by these two processes explains the current interest on reactive halogen species. Ozone is one of the key compounds of tropospheric chemistry. Upon photolysis with wavelengths below 320nm excited oxygen atoms are produced which form OH-radicals in their reaction with water. OH-radicals are the most important oxidizing species in the daytime atmosphere and responsible for the removal of VOC’s and nitrogen oxides. Since the ozone photolysis is the most important source of OH-radicals, a reduction of ozone would inevitably lead to a reduction of the OH-radical concentration and therefore of the "self-cleaning" capacity of the atmosphere.

Tropospheric ozone is also a very important absorber in the visible and infrared wavelength region and participates in the so called "greenhouse-effect" of the atmosphere. Ozone concentrations have doubled in the past 200 years due to human activities. This increase is responsible for ~15% of the antropogenically caused greenhouse effect. A complete understanding of the ozone chemistry in the troposphere, including possible influences by reactive halogens, would therefore also help to understand possible climate changes in the atmosphere.

Only recently BrO has been found at the Dead Sea, Israel with levels of up to 90 ppt [Hebestreit et al, 1998]. These high BrO concentrations were also anticorrelated with low ozone levels, similar to the situation in polar regions. No other report of BL BrO has been published.

Brauers et al., 1990, report levels of IO below 0.4 ppt in their measurements at the coast of Brittany, France, in 1988. Tuckermann et al, 1997, report an upper limit of 1.3 ppt in the Arctic. Wenneberg et al., 1996, found the total column of IO to be lower than 1013 cm-2. Also other publications [Richter at al. 1998] reported total column IO measurements but it was uncertain if IO was present in the troposphere. The first successful observation of IO as reported by Alicke et. al [1999]. At Mace Head a maximum of 6.6 ppt of IO was observed.

The sources and release mechanisms have been a topic of intense discussion for a long time. Today the following two main sources have been identified.

Photolytically unstable organohalogen compounds can act as precursors of halogen atoms in the troposphere. In contrast to the mechanisms in the stratosphere only compounds photolyzing at wavelengths above 290 nm will release RHS in the troposphere. Therefore anthropogenically produced CFC's are stable in the BL and are not a reactive halogen source. Less stable organohalogens are emitted by algae in the oceans [Khalil et al, 1993; Oertel, 1992; Rasmussen et al., 1996; Schall and Heumann, 1993; Sturges et al., 1992; Carpenter et al., 1998]. Table 2 shows the most important of these compounds.

Table 2: Organohalogen compound concentrations in the boundary layer and the respective photoytic lifetimes a.

|

Concentration |

Lifetime |

|

|

CH3Cl |

~ 630 ppt |

~ 1yr |

|

CH2Cl2 |

~ 32 ppt |

83 days |

|

CH3Br |

20 – 40 ppt |

1 - 2 yrs |

|

CHBr3 |

Days |

|

|

CH3I |

1 – 30 ppt |

3 – 4 days |

|

CH2I2 |

up to 1 ppt c |

5 min b |

|

CH2ClI |

up to 1 ppt c |

10 h |

|

CH2BrI |

up to 1 pp c |

45 min b |

a

all data from WMO Report if not noted otherwise.While many of them are present in noticeable concentrations, i.e. CH3Br, CH3I, the production rate of halogen atoms is small due to the slow photolysis of these compounds. This is the case for most compounds containing Cl and Br. In contrast many of the organo-iodides have lifetimes of the order of hours or minutes and can contribute to iodine production even at low concentrations. Especially CHI2 and CHBrI are photolyzed very fast. Recent field measurements [Carpenter et al, 1998] confirm the presence of these compounds in the boundary layer. CH2I2 concentrations and up to 1 ppt CH2BrI have been measured in Mace Head. It is possible that also other, so far unidentified, short-lived organo-iodines contribute to iodine production.

A large reservoir of halogens in the atmosphere are sea salt aerosols or salt covered surfaces. The typical halogen composition of salt is (by weight): 55.7 % Cl-, 0.19 % Br- and 2´ 10-5 % I- (in SMOW).

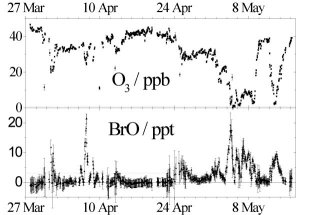

Figure 2: Heterogeneous mechanisms suspected to release RHS from sea salt

Several heterogeneous processes releasing RHS from this reservoir have been proposed. The reaction of nitrogen oxides on NaCl, KBr and salt surfaces is known to release XNO and XNO2 [Behnke et al., 1992 and 1993; Finlayson-Pitts and Johnson, 1988; Zetsch and Behnke, 1993], for example via the following reactions (see also Fig. 2):

N2O5 + NaX ®

XNO2 + NaNO3

2 NO2 + NaX ®

XNO + NaNO3

XNO and XNO2 are photolyzed fast in the early morning hours [Wayne et al., 1995] releasing halogen atoms. This mechanism would be most effective in relatively polluted air with high NOx concentrations.

Recently also the direct reaction of ozone on the surface, releasing Cl2 and Br2 has been observed in the laboratory [Oum et al., 1998a, b]

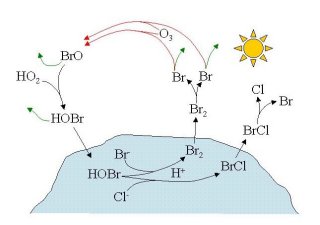

Figure 3: Bromine release mechanism by Vogt et al., 1996.

Other heterogeneous mechanisms have been proposed [Fan and Jacobs, 1992; Mozurkewitch, 1995]. Vogt et. al., 1996, proposed a mechanism based on the uptake of HOBr on acidic salt surfaces (see Fig. 3). HOBr can react on the surface with Cl- forming BrCl, which can hydrolyze back to HOBr or react with Br- to form Br2 :

HOBr (aq) + Cl- + H+ ®

BrCl (aq) + H2O (aq) BrCl (aq) + H2O (aq) ®

HOBr (aq) + H+ + Cl- BrCl (aq) + Br- ®

Br2 (aq) + Cl-

Br2 and BrCl can then return to the gas phase where they are photolysed and can react with ozone again (R1). Upon reaction 4 another HOBr molecule is formed which can again react heterogeneously on the surface.

In this reaction scheme one HOBr can release up to 2 Br atoms per cycle. If less than 50% of the bromine is lost from the cycle the number of gas phase bromine molecules increases exponentially (at the expense of Br-). Our current understanding shows that bromine is released from the autocatalytic process described in b) where chlorine is a byproduct.

The most important reaction of halogen atoms in the BL is with ozone (R1). Concurrence reactions are the ones with hydrocarbons. Recently the rate constants of halogen atoms with HC's have been measured [Atkinson et al, 1997]. Cl reaction rates are basically diffusion limited and therefore very fast. The main product of these reactions is HCl which is removed from the atmosphere very effectively, being the most important pathway of Cl removal. Bromine only reacts with unsaturated HC's and carbonyl compounds like HCHO. The rate constants are much slower than the ones for Cl . Again the formation of HBr and the following deposition is the most important removal process. Iodine is basically unreactive with HC's. The main removal process for iodine is not clear, most probably IO dimers and iodine nitrates are deposited.

All reactive halogen species react with nitrogen oxides, NO and NO2:

NO + XO ®

XONO

NO2 + XO ®

XONO2

XONO2 and XONO are photolyzed in the BL forming again XO [DeMoore et al, 1997]. The absorption cross-sections of IONO2 has been measured for the first time in the frame of the HALOTROP project and it appears to be rapidly photolyzed in the atmosphere. XONO2 and XONO might be important reservoir species of reactive halogens, especially during the night, depending on their deposition rates in the BL. Deposition of these compounds is also a possible removal pathway for RHS. The knowledge of these deposition rates, especially the ones for the different iodine compounds, are one of the most severe gaps in our understanding of iodine chemistry.

Besides the above explained ozone destruction mechanisms also the photochemical equilibrium of NO/NO2 and OH/HO2 are influenced by halogens. The ratio of NO and NO2 concentrations is normally determined by the following chemical reactions:

NO + O3 ®

NO2 + O2

O + O2 ®

O3

NO2 + hn

®

NO + O

in remote areas also the reaction of NO with HO2 becomes important:

NO + HO2 ®

NO2 + OH

If halogen atoms are present the reaction of

XO + NO ®

X + NO2

introduces another pathway to converts NO into NO2.

The ratio of NO and NO2, the Leighton ratio L, can therefore be calculated with:

Also the ratio and the absolute concentrations of OH and HO2 are affected by the presence of halogens. Besides by reaction R16 HO2 can also be converted to OH by the production of HOX (R4) followed by its photolysis (R5). Model calculations show that the HO2 concentration is decrease while [OH] increases.

Figure 4 shows a scheme for the different cycles involved in the photolytical ozone production. The solid lines symbolize the normal cycles responsible for the production of ozone in the presence of more than 10-50 ppt of NOx (=NO + NO2) and CO or Hydrocarbons. Marked in dashed lines are the different reactions of RHS which interfere with the normal mechanism. As described above these RHS open additional pathways to convert NO to NO2 and also converting HO2 to OH. In the presence of RHS the concentrations of NO and HO2 are decreased. Since the photolytic ozone production is directly proportional to these two concentrations, the production is slowed down. Effectively this can be considered as another ozone loss mechanism. In the case of 6 ppt of IO, as observed in Mace Head, this mechanism can be up to 15% of the total ozone destruction at a NOx mixing ratio of 70 ppt, being as important as cycle A.

Although many question about halogen chemistry in the troposphere ave been answered some still remain open. Also the first detection of IO and BrO at lower latitudes raised new questions which have not been considered before. Some of these questions are listed below:

What are the conditions (meteorology, tide, biology) necessary for a release of reactive iodine? What are the exact sources?

How frequent and where can elevated levels of reactive iodine be found?

What are the deposition rates for the different iodine compounds? What is the exact photolysis rate of IONO2? What is the exact mechanism of the IO + IO reaction?

Are salt pans a significant source of reactive halogen species on a global scale? What is the release mechanism of RHS on the salt pans?

How is the aerosol in Antarctica, where elevated BrO has been observed although two orders of magnitude less sulphate and nitrate are found in the aerosol, acidified? Is there a possible self acidification process? Is there a different release mechanism occurring?

What are RHS levels in the free troposphere? What is the influence on ozone chemistry there?

Does halogen chemistry have an impact not only in local regions but on a global level? What is the influence on global ozone levels and the resulting consequences for the oxidizing capacity and the global radiation budget?

Alicke, B., Hebestreit, K., Stutz, J., Platt, U., "Iodine Oxide in the Marine Boundary Layer", Nature, 397, 572 - 573, 1999

Atkinson, R., D.L. Baulch, R.A. Cox, R.F. Hampson Jr., J.A. Kerr, M.J. Rossi, and J. Troe, (1997) Evaluated kinetic, photochemical and heterogeneous data for atmospheric chemistry, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 26 (3), 521 – 1011.

Barrie L. A., Li S. M, Toom D. M., Landsberger S., and Sturges W. (1994), Measurements of aerosol and gaseous halogens, nitrates and sulphur oxides by denuder and filter systems during Polar Sunrise Experiment 1992, J. Geophys. Res., 99, 25,453-25,468.

Barrie L.A., Bottenheim J.W., Schnell R.C., Crutzen P.J. and Rasmussen R.A. (1988), Ozone destruction and photochemical reactions at polar sunrise in the lower Arctic atmosphere, Nature 334, 138-141.

Bedjanian, Y., Le Bras, G., and Poulet, G. (1997), Kinetics and mechanism of the IO + ClO reaction, J. Phys. Chem. A, 101, 4088 - 4096.

Behnke W., Krüger H.-U., Scheer V. and Zetzsch C. (1992), Formation of ClNO2 and HONO in the presence of NO2, O3 and wet NaCl aerosol, J. Aerosol Sci. 23, 933-936.

Behnke W., Scheer V. and Zetzsch C. (1993), Formation of ClNO2 and HNO3 in the presence of N2O5 and wet pure NaCl- and wet mixed NaCl/Na2SO4-aerosol, J. Aerosol Sci. 24, 115-116.

Bloss, W.J., Rowley, D.M., Cox, R.A., and Jones, R.L. (1998), Kinetic and photochemical studies of iodine oxide chemistry, Ann. Geophys. Suppl. II, 16, C717.

Bottenheim J. W., Gallant A. C. and Brice K.A. (1986), Measurements of NOy species and O3 at 82° N latitude, Geophys. Res. Lett. 13, 113-116.

Bottenheim J.W., Barrie L. W., Atlas E., Heidt L. E., Niki H., Rasmussen R. A., and Shepson P.B. (1990), Depletion of lower tropospheric ozone during Arctic spring: The Polar Sunrise Experiment 1988, J. Geophys. Res. 95, 18555 - 18568.

Brauers T., Dorn H.-P. and Platt U. (1990), Spectroscopic measurements of NO2, O3, SO2, IO and NO3 in maritime air. In Physico-Chemical behaviour of Atmospheric pollutants, Proceeding of the 5. European Symp., Varese, Italia (edited by Restelli G. and Angeletti G.), 237-242, Kluwer Academic, Doordrecht.

Carpenter, L.J., W.T. Sturges, S.A. Penkett, P.S. Liss, B. Alicke, K. Hebestreit, and U. Platt, (1998), Observation of short-lived alkyl iodides and bromides at Mace Head, Ireland: links to biogenic sources and halogen oxide production, J. Geophys Res., in press.

Cicerone R. J. (1981), Halogens in the Atmosphere, Rev. Geophys. and Space Phys. 19, 123-139.

Davis D., Crawford J., Liu S., McKeen S., Bandy A., Thornton D., Rowland F., Blake D. (1996), Potential impact of iodine on tropospheric levels of ozone and other critical oxidants, J. Geophys. Res., 101(1), 2135-2147.

De More W.B., Sander S.P., Golden D.M., Hampson R.F., Kurylo M.J., Howard C.J., Ravishankara A.R., Kolb C.E., Molina M.J. (1994), Chemical kinetics and photochemical data for use in stratospheric modelling, JPL Publication 94-26.

De Serves, C. (1994), Gas phase formaldehyde and peroxide measurements in the Arctic atmosphere, J. Geophys. Res. 99D, 25391-25398.

Fan S.-M. and Jacob D. J. (1992), Surface ozone depletion in the Arctic spring sustained by bromine reactions on aerosols, Nature 359, 522 - 524.

Finlayson-Pitts B. J. and Johnson S. N. (1988), The reaction of NO2 with NaBr: Possible source of BrNO in polluted marine atmospheres, Atmos. Environ. 22, 1107 - 1112.

Finlayson-Pitts B. J., Livingston F. E., and Berko H. N. (1990), Ozone destruction and bromine photo chemistry in the Arctic spring, Nature. 343, 622 - 625.

Hausmann M. and Platt U. (1994), Spectroscopic measurement of bromine oxide and ozone in the high Arctic during Polar Sunrise Experiment 1992, J. Geophys. Res. 99, 25,399-25,414.

Hebestreit, K., Stutz, J., Rosen, D., Matveev, V., Peleg, M., Luria, M., Platt, U., "First DOAS measurements of tropospheric BrO in mid latitudes", Science, 283, 55 - 57, 1999

Jenkin M. E. (1992), The photochemistry of iodine-containing compounds in the marine boundary layer, Report AEA Harwell, AEA-EE-0405.

Khalil, M.A.K., Rasmussen, R.A., Gundwardena, A. (1993), Atmospheric methyl bromide: Trends and global mass balance, J. Geophys. Res., 98, 2887-2896.

Kreher K. (1996), Spectroscopic Measurements of Atmospheric OClO, BrO and NO2 and their Relation to Antarctic Ozone Depletion, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Heidelberg

Kreher K., Johnston P.V., Wood S.W., Platt U. (1997), Gound-based measurements of tropospheric and stratospheric BrO at Arrival Heights (78oS), Antarctica, Geophys. Res. Lett., revised.

Laszlo, B., Huie R.E., and Kurylo J.J. (1995), The atmospheric chemistry of iodine monoxide, Poster presented at Faraday Discussion No. 100, Norwich, UK, April 19-21, 1995.

Le Bras G. and Platt U. (1995), A Possible mechanism for combined chlorine and bromine catalysed destruction of tropospheric ozone in the Arctic, Geophys. Res. Lett., 22, 599-602.

Mössinger, J.C., Shallcross, D. E. and Cox, R. A. (1998), UV-VIS absorption cross-section and atmospheric lifetimes of CH2Br2, CH2I2 and CH2BrI, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans., 94 (10), 1391 - 1396.

Mozurkewich M. (1995), Mechanisms for the release of halogens from sea-salt particles by free radical reactions, J. Geophys. Res., 100, 14,199-14,207.

Oertel, T. (1992), Verteilung leichtflüchtiger Organobromverbindungen in der marinen Troposphäre und im Oberflächenwasser des Atlantik, Ph.D. Thesis, FB2, University of Bremen.

Oum, K.W., M.J. Lakin, D.O. DeHaan, T. Brauers, and B.J. FinlaysonPitts, Formation of molecular chlorine from the photolysis of ozone and aqueous sea-salt particles, Science, 279 (5347), 74-77, 1998a.

Oum, K.W., M.J. Lakin, and B.J. FinlaysonPitts, Bromine activation in the troposphere by the dark reaction of O3 with seawater ice, Geophysical Research Letters, 25 (21), 3923-3926, 1998b.

Platt U. (1994), Differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS), In: Air Monitoring by Spectroscopic Techniques, M.W. Sigrist, Ed., Chemical Analysis Series, Vol 127, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Platt U. and Hausmann M. (1994), Spectroscopic measurement of the free radicals NO3, BrO, IO, and OH in the troposphere, Res. Chem. Intermed. 20, 557-578.

Platt U., Tuckermann M., Ackermann R., Unold W., Lorenzen-Schmidt H., Trost B., Stutz J. (1996), Halogen Oxide Measurements in the Arctic Boundary Layer and Implications for Sudden Ozone Depletion, Proceedings of the Quadrennial Ozone Symposium, L’Aquila, Italy, submitted.

Platt., U. and Janssen C. (1996), Observation and role of the free radicals NO3, ClO, BrO and IO in the Troposphere, Faraday Discuss 100, 175-198.

Pszenny A. A. P., Keene W. C., Jacob D. J., Fan S., Maben J. R., Zetwo M. P., Springeryoung M. and Galloway J. N. (1993), Evidence of Inorganic Chlorine Gases Other Than Hydrogen Chloride in Marine Surface Air, Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 699-702.

Rasmussen, R. A., Khalil, M. A. K., Gunawardena, R., and Hoyt, S. D. (1982), Atmospheric methyl iodide (CH3I), J. Geophys. Res. 87, 3086-3090.

Rasmussen, A., Kiilsholm, S., Sorensen, J.H. and Mikkelsen, I.S. (1996), Analysis of Tropospheric Ozone Measurements in Greenland, Tellus, submitted.

Richter, A., Wittrock, F., and Burrows, J. P. (1998), Gome measurements of tropospheric BrO in northern hemispheric spring, Ann. Geophys. Suppl. II, 16, C721

Sander, R. and P. J. Crutzen (1996), Model study indicating halogen activation and ozone destruction in polluted air masses transported to the sea, J. Geophys. Res. 101D, 9121-9138.

Schall, C. and Heumann, K. G. (1993), GC determination of volatile organoiodine and organobromine compounds in seawater and air samples, Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 346, 717-722.

Simon F.G., Schneider W., Moortgat G.K., Burrows J.P.(1990), A study of the ClO absorption cross-section between 240 and 310 nm and the kinetics of the self-reaction at 300 K, J. Photochem. Photobio., A 55, 1-23

Solberg, S., Schmidbauer N., Semb, A., Stordal, F. and Hov Ø, 1996, Boundary layer ozone depletion as seen in the Norwegian Arctic in spring, J. Atmos. Chem. 23, 301 - 332.

Solomon S., Garcia R.R., Ravishankara A.R. (1994), On the role of iodine in ozone depletion, J. Geophys. Res. 99, 20491-20499.

Sturges W.T., Cota G.F. and Buckley P.T. (1992), Bromoform Emission from Arctic Ice Algae, Nature 358, 660-662.

Tuckermann, M., Ackermann, R., Gölz, C., Lorenzen-Schmidt, H., Senne, T., Stutz, J., Trost, B., Unold, W., and Platt, U. (1997), DOAS-Observation of Halogen Radical- catalysed Arctic Boundary Layer Ozone Destruction During the ARCTOC-campaigns 1995 and 1996 in Ny-Alesund, Spitsbergen, Tellus, submitted.

Unold W. (1995), Bodennahe Messungen von Halogenoxiden in der Arktis, Diploma Thesis, University of Heidelberg.

Vierkorn-Rudolph B., Bächmann K., Schwarz B., Meixner F.X. (1984), Vertical profiles of hydrogen chloride in the troposphere, J. Atmos. Chem., 2, 47-63.

Vogt R., Crutzen P.J., Sander R. (1996), A mechanism for halogen release from sea-salt aerosol in the remote marine boundary layer, Nature 383, 327-330.

Wagner, T., and Platt, U. (1998), Satellite mapping of enhanced BrO concentrations in the troposphere, submitted to Nature

Wayne, R. P., G. Poulet, P. Biggs, J. P. Burrows, R. A. Cox, P. J. Crutzen, G. D. Haymann, M. E. Jenkin, G. Le Bras, G. K. Moortgat, U. Platt, and R. N. Schindler (1995), Halogen oxides: radicals, sources and reservoirs in the laboratory and in the atmosphere, Atmosph. Environ., 29, 2675-2884.

Wennberg, P.O., Brault, J.W., Hanisco, T.F., Salawitch, R.J., and Mount, G.H. (1997), The atmospheric column abundance of IO: Implications for stratospheric ozone, J. Geophys. Res., 102 (D7), 8887 - 8898.

Zetzsch C. and Behnke W. (1993), Heterogeneous reactions of chlorine compounds, NATO-ASI Series Subseries I "Global Environmental Change" Vol. 7 (edited by H. Niki and K.H. Becker), Springer-Verlag, 291-306.