The Chemistry of Nitrous Acid, HONO

Why are we interested in HONO?

Nitrous acid, HONO, is a source of the most important daytime radical: the hydroxyl radical.

The OH radical is one of the key species in photochemical cycles responsible for ozone formation,

which can lead to the so called "photochemical smog" in polluted regions.

To understand the mechanisms that lead to this ozon-smog we need to know the sources of the OH radical.

One of the most poorly understood OH sources is the formation of nitrous acid, HONO, followed by

its photolysis in sun-light [Cox, 1974: Cox ,1976; Stockwell and Calvert, 1979; Bongartz et al., 1991, 1994]

HONO + hn

®

OH + NO (1)

Although this OH source mechanism has been known for nearly three decades [Johnston and Graham, 1974; Nash, 1974; Perner and Platt, 1979; Platt et al., 1980a, b], many questions about its importance remain open.

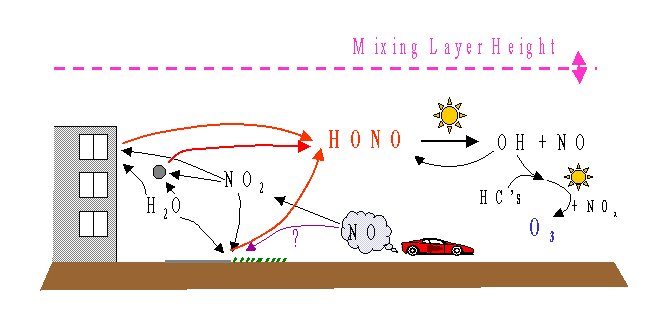

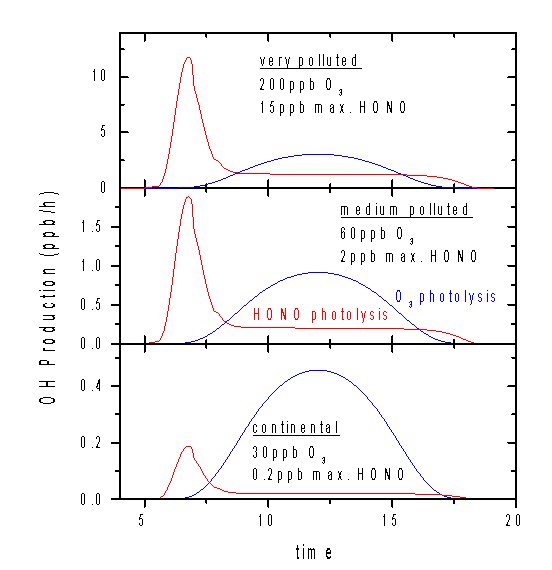

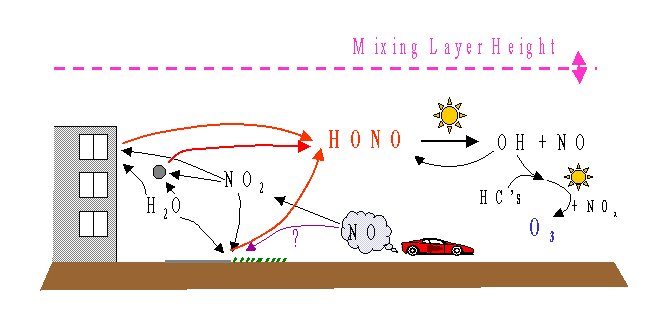

The following figure gives an overview of the chemistry of HONO which will be discussed in the next sections.

Sources of HONO

- Homogeneous Chemistry:

HONO can be formed in the reverse reaction to (1) [Pagsberg et al, 1997]:

NO + OH ® HONO (2)

This reaction is insignificant during the night, because the OH concentrations are too low.

Its significance during the day is currently unknown.

-

Heterogeneous Formation:

It is believed that HONO is mainly formed heterogeneously on surfaces in the presence of water and NO2 [Harris et al., 1982; Heikes and Thompson, 1983; Sakamaki et al., 1983; Stockwell and Calvert, 1983; Platt, 1985; Svensson et al., 1987; Jenkin et al., 1988; Lammel and Perner, 1988; Harrison et al, 1996]. The reaction mechanism can be summarized as:

H2O + 2 NO2 ®

HNO3 + HONO (2)

Laboratory measurements [Svennson et al., 1987] suggest that the HONO formation is first order in NO2 and H2O, but the exact mechanism is unknown. The reaction of water with NO and NO2 to form HONO also appears to be possible [Calvert et al, 1994], but observations indicate that NO [Stutz, 1996] is not necessary in the formation of HONO.

Unfortunately the HONO production rates determined in the laboratory are about two orders of magnitude lower that the ones observed in the atmosphere [Kessler, 1984; Sjödin, 1988; Winer and Biermann, 1994, Stutz, 1996]. Since it is not known on which surfaces HONO is produced in the atmosphere, a translation of laboratory data to the atmosphere might not be valid.

-

Formation on Soot:

Recently, the formation of HONO on soot particles in the presence of NO2 and perhaps water has been observed in the laboratory [Ammann et al.,1998; Gerecke et al., 1998]. The importance of this source is still under investigation.

-

Direct Emission:

Another source of HONO is direct emissions from combustion processes [Rondon and Sanhueza, 1988]. Studies performed in the 1980’s have suggested that HONO is emitted by diesel engines [Kessler, 1984; Pitts et al., 1984], while no HONO could be detected in the exhaust of non-diesel engines. It is uncertain whether new engines containing catalytic converters are a source of HONO. Other studies have shown that gas space heaters and stoves produce high HONO concentrations indoors [Pitts et al, 1985; Brauer et al., 1990; Vecera and Dasgupta, 1994; Febo and Perrino, 1995].

Sinks of HONO

The most important sink of HONO is photolysis (see reaction 1). The heterogeneous self-reaction of HONO has been investigated in the laboratory at high HONO concentrations [Febo et al, 1995], but it is unlikely that it plays a role in the atmosphere. HONO can also react with secondary and tertiary amines, forming carcinogenic nitrosamines [Pitts et al, 1978]. While this is not an important loss process, it has a direct impact on human health [Beckett et al., 1995; Rasmussen et al., 1995].

Observation of HONO and the Implication for Atmospheric Chemistry

Observations of HONO in the atmosphere show typical diurnal cycle.

Since the major loss process is photolysis, HONO builds up during the night. At sunrise it is photolyzed into OH radicals and NO and its concentration drops. During the early morning hours HONO can be the most important source of OH radicals in the polluted atmosphere, as will be shown later. The concentration remains low during the day and rises again after sunset.

Observations of HONO in the polluted atmosphere often show nighttime mixing ratios of more than 10 ppb.

Table 1 gives an overview of several observations of HONO in the polluted and remote atmosphere. No reliable daytime observations have been reported, but HONO mixing ratios up to 1 ppb at low sunlight intensities appear to be possible. A quantification of the daytime OH production by HONO photolysis has not been reported.

Table 1: Exaples of some maximum mixing ratios of HONO in the atmosphere and the quotient of HONO and NO2

| |

Technique |

Max. HONO

ppb |

HONO/NO2

% |

|

|

Juelich, Germany |

DOAS |

0.8 |

2.4 |

Perner & Platt 1979 |

|

Deuselbach, Ger. |

DOAS |

< 0.1 |

< 0.06 - < 2 |

Perner & Platt 1979 |

|

Los Angeles |

DOAS |

8 |

1 – 13 |

Harris et al. 1982 |

|

Göteborg, Swe. |

Denuder |

0.26 (avg.) |

- |

Ferm et al. 1983 |

|

Long Beach |

DOAS, Den. |

15 |

2.5 |

Appel et al. 1990 |

|

Ispra, Italy |

OPSIS – DOAS |

2 |

2 |

Notholt et al. 1992 |

|

Birmingham, UK |

Den.,Cont. Anal. |

10 |

1.5 |

Harrison et al. 1994 |

|

Milano, Italy |

Denuder |

17 |

up to 12 |

Febo et al. 1993, 1996 |

|

Zürich,Switz. |

Wet Wall Den. |

3.4 |

3.9 (avg.) |

Zellweger et al. 1997 |

How important is HONO as OH source?

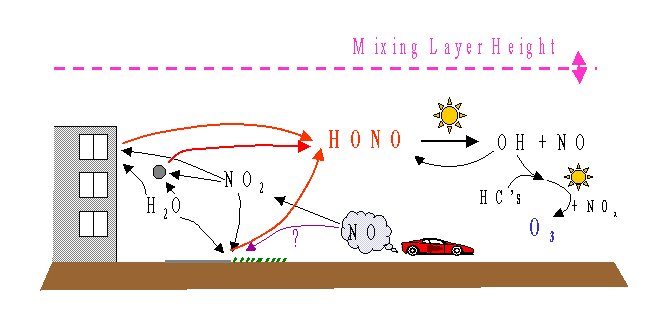

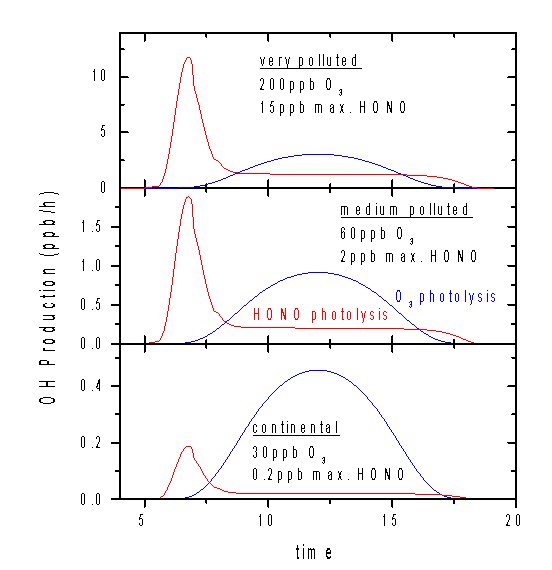

Simplified model calculations can be performed using varying HONO production rates explaining 0.2 ppb, 6 ppb, and 15 ppb, maximum HONO nighttime concentrations. These calculations show that, in the early morning, OH production from HONO photolysis exceeds OH production from the photolysis of ozone (figure 1). Later in the day, ozone photolysis dominates. In heavily polluted regions, HONO photolysis can be as much as 50% of the total OH production during the day (see following figure).

The numbers used for this calculation, as well as the OH production integrated over 24 hours, are displayed in table 2. Even integrated over a 24 hour period, the OH production by HONO photolysis can be comparable to the one by ozone photolysis.

Table 2: HONO formation rates used in the model calculations and the integrated OH production over 24 hours.

|

[O3]

ppb |

HONO Formation

ppb/h |

OH Production in 24h

ppb |

|

O3 Photolysis |

HONO Photolysis |

|

Very Polluted |

200 |

1.5 |

18.1 |

24.1 |

|

Medium P. |

60 |

0.2 |

5.4 |

3.9 |

|

Cont. Backgr. |

30 |

0.02 |

2.7 |

0.4 |

Why do we still not Understand HONO Chemistry?

The problem with HONO is that its concentration is strongly influenced by meteorological effects,

i.e. the change from nighttime to daytime chemistry.

During the night the boundary layer is at a much lower altitude, sometimes below 100m, than during the day,

where it typically is located between 1000 m and 1500m.

If HONO is formed close to the ground, the observed concentration at night will only reflect the lowest part of the troposphere.

When the boundary layer moves upward during the morning the HONO is diluted.

Assuming a nighttime boundary layer height of 150m and no HONO above the inversion,

the dilution factor referring to a daytime inversion at 1500m is 10.

Therefore, the measured source strength of HONO would be lower by a factor of 10. Even in this case HONO photolysis remains the most important OH source in the morning while it will only contribute ~10% of the OH production over a 24 hour period. At lower pollution levels the importance of HONO photolysis is smaller.

Why do we want to know more about the Chemistry of HONO?

A better understanding of the formation of HONO and its importance as a source of OH-radicals is highly desirable

for the improvement of air pollution models. So far, none or only very oversimplified HONO production

mechanisms, i.e. converting 10% of the NO2 into HONO, are used in these models.

As shown above, a better understanding of HONO chemistry might have a severe impact on

these models, our understanding of photochemical smog formation, and possible future political decisions regarding emission control strategies.

Open Questions

- How is HONO formed in the atmosphere, and which parameters influence its formation?

- Do the observations agree with mechanism derived in laboratory studies?

- On which surfaces is HONO formed in the atmosphere?

- What are the HONO production rates during the night and during the day?

- Is direct emission of HONO by combustion processes an important source?

- How significant is OH formation by HONO photolysis?

References

-

Ammann, M., M. Kalberer, D. T. Jost, L. Tobler, E. Rössler, D. Piguet, H. W. Gäggler, and U. Baltensperger, "Heterogeneous Production of Nitrous Acid on Soot in Polluted Air Masses," Nature, 395, 157-160, 1998.

-

Appel, B.R., A.M. Winer, Y. Tokiwa, H.W. Biermann, "Comparison of atmospheric nitrous acid mesurements by annular denuder and differential optical absorption systems", Atmos. Environ., 24 A, 611-616, 1990.

-

Beckett, W. S., M. B. Russi, A. D. Haber, R. M. Rivkin, J. R. Sullivan, Z. Tameroglu, V. Mohsenin, and B. P. Leaderer, "Effect of Nitrous Acid on Lung Function in Asthmatics: A Chamber Study," Environ. Health Perspect, 103, 372-375., 1995.

-

Bongartz, A., J. Kames, and U. Schurath, "Experimental Determination of HONO Mass Accomodation Coefficients using two Different Techniques", J. Atmos. Chem., 18, 149 - 169, 1994.

-

Bongartz, A., J. Kames, F. Welter, and U. Schurath, "Near-UV Absorption Cross Sections and Trans/Cis Equilibrium of Nitrous Acid", J. Phys. Chem., 95, 1076 - 1082, 1991.

-

Brauer, M., P. B. Ryan, H. H. Suh, P. Koutrakis, J. D. Spengler, N. P. Leslie, and I. H. Billick, "Measurements of Nitrous Acid Inside Two Research Houses," Environ. Sci. Technol., 24, 1521-1527, 1990.

-

Calvert, J.G., G. Yarwood, and A.M. Dunker, "An evaluation of the mechanism of nitrous acid formation in the urban atmosphere", Res. Chem. Intermed., 20, 463-52, 1994.

-

Cox, R.A., R.G. Derwent, The ultra-violet absorption spectrum of gaseous nitrous acid, J. Photochem., 6, 23-34, 1976.

-

Cox, R.A., "The photolysis of gaseous nitrous acid, J. Photochem., 3, 175-188, 1974.

-

Febo, A. and C. Perrino, "Prediction and experimental evidence for high air concentration of nitrous acid in indoor environment", Atmos. Env., 25, 1055-1061, 1991.

-

Febo, A., C. Perrino and M. Cortiello, "A denuder technique for the measurement of nitrous acid in urban atmospheres", Atmos. Env., 27, 1721-1728, 1993.

-

Febo, A., C. Perrino, M. Gherardi and R. Sparapani, "Evaluation of a high-purity and high-stability continuous generation system for nitrous acid", Env. Sci. and Technol., 29, 2390-2394, 1995.

-

Febo, A., C. Perrino, and I. Allegrini, "Measurement of nitrous acid in Milan, Italy, by DOAS and diffusion denuders", Atmos. Environ., 30, 3599-3609, 1996.

-

Febo A. and C. Perrino, "Nitrous acid generation, fate and detection", Encyclopaedia of environmental analysis and remediation, 3015-3035, 1998.

-

Finlayson-Pitts, B. J., and J. N. Pitts, Jr., Atmospheric Chemistry: Fundamentals and Experimental Techniques, Wiley, 1986.

-

Ferm, M., A. Sjoedin, H., "A simple method for determination of gaseous nitrous acid in the atmosphere", Swed. Environ. Res. Inst., 1983.

-

Gerecke, A., A. Thielmann, L. Gutzwiller, M. J. Rossi, "The Chemical Kinetics of HONO Formation Resulting from Heterogeneous Interaction of NO2 with Flame Soot," Geophys. Res. Lett., 25, 2453-2456, 1998.

-

Harris, G.W., W.P.L. Carter, A.M. Winer, J.N. Pitts, U. Platt, D. Perner, "Observations of nitrous acid in the Los Angeles atmosphere and implications for the predictions of ozone-precursor relationships", Environ. Sci. Technol., 16, 414-419, 1982.

-

Harrison, R.M., J.D. Peak, and G.M. Collins, "Tropospheric cycle of nitrous acid", J. Geophys. Res., 101, 14429-14439, 1996.

-

Heikes, B.G., A.M. Thompson, H., "Effects of heterogeneous processes on NO3, HONO, and HNO3 chemistry in the troposphere", J. Geophys. Res., 88, 10,883-10,895, 1983.

-

Jenkin, M.I., R.A. Cox, D.J. Williams, "Laboratory studies of the kinetics of formation of nitrous acid from the thermal reaction of nitrogen dioxide and water vapour", Atmos. Environ., 22, 487-498, 1988.

-

Johnston, H.S., R. Graham, S., "Photochemistry of NOx and HNOx compounds", Can. J. Chem., 52, 1415-1423, 1974.

-

Kessler, C., Gasfoermige salpetrige Saeure (HNO2) in der belasteten Atmosphaere, PhD Thesis,University of Cologne, 1984.

-

Lammel, G., D. Perner, "The atmospheric aerosol as a source of nitrous acid in the polluted atmosphere", J. Aerosol Sci., 19, 1199-1202, 1988.

-

Nash, T., "Nitrous acid in the atmosphere and laboratory experiments on its photolysis", Tellus, 26, 175-179, 1974.

-

Notholt, J., J. Hjorth, F. Raes, "Formation of HNO2 on aerosol surfaces during foggy periods in the presence of NO and NO2", Atmos. Environ., 26A, 211-217, 1992b.

-

Pagsberg, P., E. Bjerbakke, E. Ratajczak, and A. Sillesen, "Kinetics of the Gas Phase Reaction of OH + NO (+M) -> HONO (+M) and the Determination of the UV Absorption Cross Section of HONO", Chem. Phys. Lett., 272, 383 - 390, 1997.

-

Perner, D., U. Platt, "Detection of nitrous acid in the atmosphere by differential optical absorption", Geophys. Res. Lett., 6, 917-920, 1979.

-

Pitts, J.N., H.W. Biermann, A.M. Winer, E.C. Tuazon, M., "Spectroscopic identification and measurement of gaseous nitrous acid in dilute auto exhaust", Atmos. Environ., 18, 847-854, 1984.

-

Pitts, J.N., T.J. Wallington, H.W. Biermann, A.M. Winer, "Identification and measurement of nitrous acid in an indoor environment", Atmos. Environ., 19, 763-767, 1985.

-

Platt, U., D. Perner, G.W. Harris, A.M. Winer, J.N. Pitts, "Observations of nitrous acid in an urban atmosphere by differential optical absorption", Nature, 285, 312-314, 1980a.

-

Platt, U., D. Perner, "Direct measurements of atmospheric CH2O, HNO2, O3, NO2, and SO2 by differential optical absorption in the near UV", J. Geophys. Res., 85, 7453-7458, 1980b.

-

Platt, U., and D. Perner, "Measurements of atmospheric trace gases by long path differential UV/visible absorption spectroscopy", in Optical and Laser Remote Sensing, edited by D.A. Killinger, and A. Mooradien, pp. 95-105, Springer Verlag, New York, 1983.

-

Platt, U., The origin of nitrous and nitric acid in the atmosphere, 299-319 pp., W. Jaeschke, Springer Verlag, 1985.

-

Platt, U., "Differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS)", Chem. Anal. Series, 127, 27 - 83, 1994.

-

Rasmussen, T. R., M. Brauer, and S. Kjærgaard, "Effects of Nitrous Acid Exposure on Human Mucous Membranes," Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med, 151, 1504-1511, 1995.

-

Rondon, A., E. Sanhueza, "High HONO atmospheric concentrations during vegetation burning in the tropical savannah", Tellus, 41B, 474-477, 1988.

-

Sakamaki, F., S. Hatakeyama, H. Akimoto, "Formation of nitrous acid and nitric oxide in the heterogeneous dark reaction of nitrogen dioxide and water vapor in a smog chamber", Int. J. Chem. Kinet., XV, 1013-1029, 1983.

-

Sjoedin, A., Smog, "Studies of the diurnal variation of nitrous acid in urban air", Environ. Sci. Technol., 22, 1086-1089, 1988.

-

Stockwell, R.W., and J.G. Calvert, "The Near Ultraviolet Absorption Spectrum of Gaseous HONO and N2O3", J. Photochem., 8, 193 - 203, 1978.

-

Stockwell, W.R., J. Calvert, "The mechanism of NO3 and HONO formation in the nighttime chemistry of the urban atmosphere", J. Geophys. Res., 88, 6673-6682, 1983.

-

Stutz, J."Messung der Konzentration troposphärischer Spurenstoffe mittels Differentieller-Ptischer-Absorptionsspektroskopie: Eine neue Generation von Geräten und Algorithmen", Ph.D. Thesis Univ. Heidelberg, Heidelberg, 1996.

-

Stutz, J., Platt, U., "Numerical analysis and estimation of the statistical error of differential optical absorption spectroscopy measurements with least-squares methods", Appl. Optics, 35, 6041-6053, 1996.

-

Svensson, R., E. Ljungström, O. Lindqvist, H. "Kinetics of the reaction between nitrogen dioxide and water vapour", Atmos. Environ., 21, 1529-1539, 1987.

-

Vasudev, R., "Absorption Spectrum and Solar Photodissociation of Gaseous Nitrous Acid in the Actinic Wavelength Region", Geopys. Res. Lett., 17 (12), 2153 - 2155, 1990

-

Vecera, Z., and P. K. Dasgupta, "Indoor Nitrous Acid Levels. Production of Nitrous Acid from Open-Flame Sources," Intern. J. Environ. Anal. Chem., 56, 311-316, 1994.

-

White, J. U., "Long Optical Paths of Large Aperture," J. Opt. Soc. Am., 32, 285-288, 1942

-

White, J.U., Very long optical paths in air, J. Opt. Soc. Am, 66, 411-416, 1976.

-

Winer, A. M., and H. W. Biermann, "Long Pathlength Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS) Measurements of Gaseous HONO, NO2, and HCHO in the California South Coast Air Basin," Res. Chem. Intermed., 20, 423-445, 1994.

D-3